Food loss and waste (FLW) has become a widespread catastrophe that is witnessed across the world and that has massive repercussions for the environment, society and the financial bottom line. It is without doubt humankind’s greatest inefficiency.

How much is lost and wasted?

In today’s world, 1.2 billion people are overfed while 800 million are under-nourished. However, we still currently produce enough food for 10 billion people, and that means everyone today and those expected in 2050. Recent studies conducted by the FAO, estimate that one third of all the food intended for consumption is lost or wasted along the Supply Chain (Gustavsson et al. 2011). This means that each year 1.3 billion metric tons of food is thrown away around the world, amounting to 8% of annual greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). If food waste were a country, it would be the third largest emitter behind the US and China (Hanson 2016; FAO 2013). The United Nations has therefore set a clear path for the world to follow through its Sustainable Development Goals of “halving per capita global food waste across Supply Chains” and “substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycle, and reuse” (FAO 2016). It is now down to countries, businesses, and individuals to respond accordingly.

What is wasted?

When looking at FLW it is important to understand that when throwing away food, it is not only the end produce that is ending in the bin. It is also the resources within it; the so-called ‘foodprint’. To produce an apple, for example, takes soil, water, energy, manpower and fuel among other factors. Then add all the resources needed to ship this apple from one continent to another. Wasting that apple therefore means wasting all those scarce resources that could have been employed for other purposes. FLW is hence responsible for a quarter of all deforestation around the world, causing species extinction and environmental degradation. These costs are often undervalued, underreported and even hidden from the true impact on the planet and the bottom line. According to FAO, all these human costs – economic, social and environmental – associated with FLW would equal to $ 2.6 trillion each year, roughly the GDP of France (FAO 2014).

Where and Why is it wasted?

Everywhere and anywhere. The only difference is that across the world it takes place for different reasons. In developing nations such as in Africa, consumers value food but simply lack the technology, expertise and facilities to overcome certain barriers leading to waste, especially near the farm. While in developed nations, it is us consumers that primarily waste perfectly edible food due to sheer abundance and disassociation from the source.

Farmers face the struggle of adverse weather conditions and may also end up throwing large quantities of their harvest to waste as they do not adhere to quality standards and product specifications set by legislation or by supermarkets. Additionally, as more food is transported longer distances, the cool chain is playing an even more important role. Some airports may not have the required infrastructure or capacity and may therefore at times leave pallets in the blistering heat rather than in refrigerated areas. They may also lack the training and competencies to handle certain types of food, hence bruising, damaging or even spoiling food in the process. On the other side of the spectrum, supermarkets overfill their aisles with food on display, reject any misshaped produce from farmers, and set expiration labels hard to interpret for modern consumers. Overcautious consumers may not even consider buying certain items based on their appearance or their near expiry shelf life. Consumers also tend to overbuy and overfill their fridges, leading to significant waste in the household. Lastly, restaurants, hotels, cruise lines and canteens serve over-size buffets to please the consumer, prepare massive portions to appeal the eye, and decide to overcook on meals rather than to run out unexpectedly. We as humanity have lost our appreciation and respect for food. FLW truly occurs at every stage of the Supply Chain, and therefore the problem needs to be addressed systemically. Rather than decomposing reality into parts, one should look at the problem contextually and holistically in terms of mutually dependent and interrelated components within a system.

How can it be prevented?

As Einstein rightly suggested: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” This holds also true when looking at the current issue of FLW in the food system. Rather than seeing one single actor within the Supply Chain as the responsible low hanging fruit, it is an overarching system that is failing. Currently, humankind’s mindset was based on a cradle-to-grave principle of taking, making, and wasting. This linear paradigm has caused humanity to extract huge quantities of raw materials that may have seemed infinitely available, and then dispose of its waste on landfill mountains. There, food leftovers are not only treacherous for air or water pollution, but they also emit significant amount of methane, thirty times more potent as a heat-trapping gas than carbon dioxide. Now also add the large amounts of scarce resources depleted in the process, never to be used again. Hence our primary solution in solving this problem should be to prevent it in the first place. So how can it be prevented?

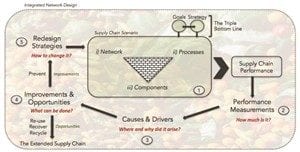

To better understand the role of Supply Chain Management in the FLW issue, I developed the ‘Eco-effectiveness Model of FLW’. The model suggests that the goal should not be to reduce, minimise or avoid FLW but to systemically eliminate the very concept of it through the eco-effective design of the Supply Chain. While eco-efficiency suggests producing more goods with fewer resources and less waste, eco-effectiveness means to see waste as food and resource within a closed loop, cradle-to-cradle approach.

The Eco-effectiveness Model of FLW (Schuler, 2017).

A business should first snapshot their Supply Chain scenario, including their network (interrelationships and interactions with other stakeholders), their processes (intra- and inter-organisational), and their components (configuration and structure in place). Once this is done, they need to measure their performance based on how much food has been wasted. The common notion of “one can only manage, what one measures” holds true. Hence, businesses need to map out and monitor the waste they are currently discarding. This can be as simple as segregating waste streams, putting a balance in place to weigh discards, and eventually track daily waste systematically. This means understanding and tracing what food items were wasted and when they were wasted. Once this data has been collected, the causes and drivers have to be identified, in terms of where and why this waste arose in the first place, and then evaluated in terms of highest contributing factor.

How can we adopt a circular approach?

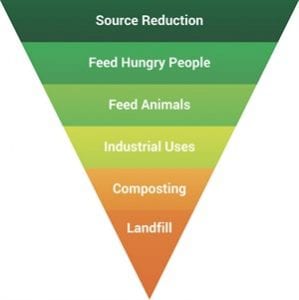

For all the waste that in a particular instance cannot be avoided or prevented, a business should extend their Supply Chain and look for opportunities in re-using, recovering or recycling it within a circular, sharing economy. This means that the food that was otherwise discarded will end up in the hands of others and/or will be repurposed for a different use. Clearly depicted on the Food Recovery Hierarchy Model, other people in society should be the first ones to be kept in mind with surplus food. This can take place in terms of giving leftovers to charities, food banks or homeless communities, or selling misshaped or near expiry produce for a reduced price to those with lover budgets. A sharing economy should be encouraged, in which people invite others to take what is left, and hence sharing rather than discarding it. For food that is no longer edible for humans, one can divert it to cattle or pig feed. Rather than using soy beans grown on decimated Amazon rainforest land, it is not just morally right but can also become financially lucrative through collaborative partnerships. Hence, to see one man’s trash as my own treasure. Another solution can also be to use bio digesters or composts to recycle waste as a resource into fertilisers, or to use it as a source of energy in the name of biogas. The overall mindset should be to recycle or at times even upcycle FLW by reconverting it into a different use. The waste from one production becomes the resource for the next. The opportunities are simply endless and new, exciting startups are leading the way ensuring that those solutions are available on the market. Landfills and incineration, whereby valuable resources end up in smoke, should be seen as a redundant last resort.

The Foodservice Operator’s Guide.

But how can we avoid that waste? In order to avoid today’s waste tomorrow, improvements have to be made, based on the measurements and observations made. To make the Supply Chain eco-effective, changes will have to be made in the design of the Supply Chain, particularly the Supply Chain scenario. These remedies or redesign strategies can include anything, ranging from better collaboration or communication in terms sharing of best practices, knowledge and information, to better infrastructure or upgraded forecasting technology. Capacity-building and training become a vital part in moving toward a sustainable solution. The rationale is that this new redesigned Supply Chain will then relatively accumulate a smaller amount of FLW with fewer or none disturbances eventually leading to less waste. This process is repeated, and it continuously improves the Supply Chain, bringing the system closer to a sustainable Supply Chain.

Ultimately, I believe that businesses need to start looking at sustainability through a different lens and move towards a cradle-to-cradle ideology similar to nature. FLW should be on everyone’s agenda, particularly as climatic changes are already well underway and deem to become worse in years to come. Expensive corporate social responsibility reports, that overpromise and often under-deliver on targets that simply cannot be reached with current operations, need to come to an end. Sustainability should instead be completely integrated into the business culture, in its operations, and across the supply chain network. This means that green corporate goals need to be translated into achievable, strategic and lucrative incentives. It may be true that investment costs to rethink and reshape the food system may at first seem elevated, but they are compensated by long-term benefits of increased volumes of food available for sale, increased market value, and improved nutritional value, while also aligning the business with the UN SDG Goals 3, 12, and 13. It is clear that in my eyes, there is no greater opportunity for humanity than tackling the scandalous tons of food thrown away each and every day around the world – it is a pressing issue that is economically damaging, environmentally threatening, and simply morally irresponsible.

References

EPA, 2017. Food Recovery Hierarchy Model. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

FAO, 2013. Food wastage footprint. Impacts on natural resources. Summary Report.

FAO,2014. Food Wastage Footprint: Full cost-accounting, Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3991e.pdf.

FAO, 2016. Food and Agriculture – Key to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable.

Development, Rome.

Gustavsson, J. et al., 2011. Global Food Losses and Food Waste – Extent, causes and prevention, Rome.

Hanson, C., 2016. From “why” to “how”: Reducing food loss and waste. World.

Resources Institute.

Schuler, P., 2017. Food Loss and Waste in the fresh potato supply chain of Denmark. Copenhagen Business School. Available at: http://studenttheses.cbs.dk/xmlui/handle/1.

0417/6266Food Loss and Waste, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen.