Introduction

Many companies increasingly engage in collaboration because a company that wants to survive in a globalised world needs to be able to leverage partners’ capabilities around the world, building innovation networks and supply chains that become increasingly complex (Kreye et al., 2013). One area of collaboration is engineering service provision, where traditional manufacturing companies provide through-life support for their products and equipment. To support their service business, providers of engineering services need to develop and implement appropriate capabilities to realise such a shift and to offer different levels of service complexity. In particular, the development of contractual and relational capabilities is important for the success to meet new market conditions and realise emerging business opportunities. Without appropriate contractual and relational capabilities, providers are not able to write, interpret and manage complex contracts govern these integrated solutions. Moreover, without appropriate relational capabilities, organisations would not be able to build strong inter-personal and inter-organisational relationships with their customers.

Engineering services can be classified according to their level of service complexity as many providers offer agreements of different levels of service complexity. Maintenance or after-sales services require less complexity with regard to the operational processes and delivery system than performance-based services. Thus, it can be expected that the provider’s contractual and relational capabilities required to offer and receive PSSs differ depending on the level of service complexity. For example, Grundfos, a Danish manufacturer of water pumps and pump systems, offer services ranging from basic support in terms of repair and exchange to improved reliability and performance of their equipment. Another example is Vestas, a Danish manufacturer of wind turbines, who offers services of varying degrees of complexity ranging from spare parts to availability contracts guaranteeing the performance of their turbines. Both companies needed to build up strong working relationships, based on contracts and trust, to offer PSS offerings to its customer base.

Danish industry has many successful examples of companies collaborating globally and the insights from one such company are described in this article. We will use an exemplar Danish company to demonstrate how they manage their capabilities for successful customer relationships under different levels of service complexity. We worked with this Danish service provider and two of their customers who received services of different levels of service complexity – Customer A with low and Customer B with high service complexity. We will show the differences in the contractual and relational capabilities the service provider employs with their customers depending on the level of service complexity.

Findings from a Danish provider of engineering services

Looking at two service relationships with two customers – one of low complexity and one of high complexity – which were both based on a long-standing relationship between provider and customers. However, interviews highlighted that this relationship changed driven by the shifts in the business context.

Contextual setting

Similar to business relationships in general, market conditions have become increasingly complex bounding the provider’s and customers’ possibilities for interaction and increasing their responsibility. Specifically, EU-wide tendering processes define the interaction between seller and buyer with tight definitions of what information is exchanged, how it is communicated, how much contact is allowed. The EU tendering process is aimed at increasing competition by requesting the customer to publish their requirements for a product or service they wish to purchase – a CT scanner, a support contract for machinery or similar – and invite bids for these requirements. All submitted bids are evaluated objectively based on predefined and published criteria such as the price, fulfilment of the requirements, performance and workflow. This tendering process increased the level of competition but also limited the amount of direct communication between provider and customer.

Contractual capabilities

To deal with the different levels of service complexity of the contracts with Customer A and Customer B, our service provider utilised modularity, where specific service activities were defined and could be combined by the customers depending on their individual needs. As such, we did not observe a higher level of contractual capabilities in terms of writing, negotiating, monitoring and enforcing contracts in general or any difference between the two customers and their arrangements of services with different levels of complexity. Our Danish service provider has contracts consisting of three pages which detail the following infomration: (i) a title page that listed the serviced product(s) with its specifications such as product type and model number; (ii) one page describing the service activities and (iii) one page of contract specific information such as agreed response time, telephone numbers in case telephone support was part of the agreement, the contract date and the signatures of contractual partners. Only marginal differences exist between the levels of service complexity.

The service modularity is a stratgy that is defined centrally within the service provider and adjusted to specific customer needs locally. The definition of the service modularity was undertaken centrally within the PSS provider and the different modules are the same for each customer. However, the contract negotiation including issues such as the combination of different service modules and response times were negotiated locally with each customer individually, meeting customer’s needs. The modularity offered a very simple but also comprehensive list of service activities.

Another reason for the lack of a difference in contractual capabilities for different service omcplexity levels is the high level of regulations within the EU tendering process. These tight regulations have legal implications by themselves for all involved partners with strong sanctions for violating them. Thus, opportunistic behaviour is mitigated by European regulations allowing the companies acting within these boundaries to limit their contractual arrangement to the specific needs of the relaitonship. These findings illustrate that even though the contractual capabilities were not a distinguishing feature with regards to different levels of service complexity across the investigated case studies, they were still essential to ensure a high level of service quality to be delivered throughout the contract period. They ensured that occurring problems were addressed in a timely manner to avoid any escalation within the service relationship.

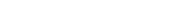

Figure 1: Contractual and relational capabilities for service delivery in the business context of tight European regulations, defined tendering processes and service modularity.

Relational capabilities

Relational capabilities are a key aspect of both customer relationships, despite the high level of regulation. The customer’s experience with service provider as well as with their equipment is an important influence on their decision during subsequent tendering processes. The service provider used primarily their service engineers to build a strong relationship, characterised by, for instance, increased information exchange. The customers echoed this importance of building up and maintaining relational capabilities particularly when managing the close relationship with service engineers. Both customers can contact their service engineer directly and get him to help with break-downs or other issues.

The service provider applies higher levels of relational capability for higher levels of service complexity, i.e. Customer B (service of high complexity) received closer and more intense attention than Customer A (service of low complexity). As such, the provider utilises centrally defined procedures in connection with customer-specific experiences. In other words, service activities are defined as formal routines and procedures prescribing the customer interaction and are implemented through the specific service engineer and service manager based on the specific customer needs, skills and knowledge. Both parts of the service relationship – centrally defined and locally implemented activities – define the provider’s relational capabilities and depend on the level of service complexity.

Case A (low service complexity) was characterised by four annual visits for preventative maintenance activities where the system was inspected and recommendations made. Inteaction is relatively formal – appointments would be agreed and a service protocol with recommendations sent to the Customer A after the inspection. To cover firstline-emergencies, Customer A employs own engineers that could perform simple repairs themselves. This strategic decision to keep some service capabilities insourced may in turn have influenced Customer A’s acquisition of a service contract with a low level of service complexity; however, it also meant that the provider needed to have low level of relational capability.

In contrast, the relationship with Customer B is much closer, meaning that the service provider applies higher levels of relational capabilities. When the provider’s engineers are on site for the preventative maintenance inspections, they also consider whether there are additional issues they could solve during their visit. In addition, the customer receives much closer attention even if they do not have any issues with the product – sometimes the provider’s engineers would just go on site to have a chat about problems or follow-ups.

Conclusions

Strategically categorising your offerings and customers into clusters is one of the basic strategic tools a service provider has. We showed in this article that this needs to be complemented by a differentiation of capabilities as summarised in Figure 1. Given the specific developments in the business context, such as the introduction of the tendering process and the tight regulations within Europe as well as the provider’s strategy to structure their service offerings into modules of activities that the customers can pick and choose from, the service provider does not need to apply higher levels of contractual capabilities for their contracts of higher levels of service complexity. In other words, the provider can build and maintain a steady ability to write, negotiate, monitor and enforce contracts in their service business irrespective of the level of agreement with their customers. In contrast, the relational capabilities differ immensely between levels of service complexity

This means that service providers need to be aware of the level of service complexity to ensure that they develop and maintain an appropriate level of contractual and relational capabilties. Companies such as Grundfos and Vestas but also Siemens or FLSmidth typically increase the complexity of their servic eofferings and therefore need to acquire capabilities in two complementary directions. First, relational capabilities need to complement service capabilities, in particular at higher levels of service complexity, because enhanced relational capabilities improve the customer’s perception of service quality. Second, there is a need for contractual capabilities to complement the relational ones. This will ensure that services are provided more effectively and equipment in the water, wind, healthcare and cement industries function better and offer higher benefits for consumers.

References:

Argyres, N. & K. J. Mayer 2007. Contract Design as a Firm Capability: An Integration of Learning and Transaction Cost Perspectives. The Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1060-1077.

Helfat, C. M. & M. A. Peteraf 2003. The Dynamic Resource-Based View: Capability Lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(997-1010.

Kreye, M. E., L. B. Newnes & Y. M. Goh 2013. Information availability at the competitive bidding stage for service contracts. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 24(7), 1-33.

Menguc, B., S. Auh & P. Yannopoulos 2014. Customer and Supplier Involvement in Design: The Moderating Role of Incremental and Radical Innovation Capability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(2), 313-328.

Contractual and relational capabilities

A capability is the ability of an organisation to perform coordinated activities utilising resources to achieve a goal and to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base (Helfat and Peteraf, 2003). It describes a company’s ability to deploy resources or transfer input into desirable outputs (Menguc et al., 2014). Contractual capabilities are a company’s ability to write, negotiate, monitor and enforce contracts (Argyres and Mayer, 2007). They ensure the implementation of the contractual agreement, especially when disagreements between the partners in the service relationship arise through contractual rules and safeguards defining the specify roles and responsibilities of partnering organisations.

Relational capabilities are an organisation’s ability to perform in and benefit from inter-organisational relationships. They focus on creating relationship-specific assets and effectively create, exchange and exploit knowledge and skills through the application of social routines and behaviour.

Author biographie:

Melanie E. Kreye, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Management Engineering, Technical University of Denmark (DTU). Her research focuses on uncertainty in different industrial and academic areas. These areas include uncertainty management within the relationship between service provider and customer and uncertainty perception for decision support and New Product Development (NPD). Her research has been published in high-quality international journals such as Omega – The International Journal of Management Science and Production Planning and Control.