What were we made for?

20 years of surveys of women in logistics/SCM

Women have served in some capacity in the logistics arena for a long time but not often reaching the management or leadership positions. With the title reference to the movie “Barbie”, my claim is that we have come a long way but are made for more. In this article, I will share some experiences as one of the first female professors in the logistics management field, and next I will present results of the survey “Women in Logistics”, that I was at the forefront of for twenty years.

I remember attending my first professional conference as a new doctoral student in 1979. The organization was then called the National Council Physical Distribution Management (NCPDM, the first of three names for the same organization). The number of women attending most probably could be counted on two hands, maybe one.

In those early days, we tried to fit in. The dress of the day was a suit and a bow tie. One of my friends said it made her feel like a puppy with a bow under its chin. Fortunately, dress for success has a broader definition today.

When I was hired after my PhD in 1982, I was the only female faculty member in the department. That would remain for several years, and I would be the first tenured female in the department. I found out later that part of the money to hire me came from a university pool to hire women. I felt degraded. I want to be judged on my performance, not some designation. I felt more degraded when I found out how much less I was paid for many years. However, things did work out and I had a nice career and now a nice pension.

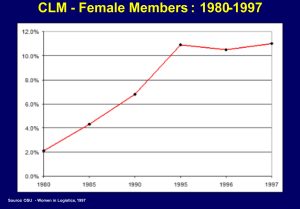

When we started surveying the women in logistics in 1997, at the suggestion of our chaired professor, Bud LaLonde, we hand counted and estimated female names as the organization, now called Council of Logistics Management (CLM), did not keep records on members’ sex. From that hand count, there were approximately 2.1% females in 1980 and 11% in 1996 (See figure 1). 2023 membership is approximately 30%. Members are primarily managers, directors, VPs, and presidents or CEOs.

Figure 1: 1997 Survey

In the 1997 report, we stated that the purpose of the study was to collect baseline information about the CLM women members. Specifically, the team sought to obtain insight into the following questions:

What has been the role of women in CLM since 1980?

What are the female logistics executive demographic profiles?

What are the work environment profiles for the female logistics executives?

What are the current and future career patterns for the female

logistics executives?

What are the most critical problems and attitudes for the 21st

century?

These questions stayed essentially the same for most of the surveys, through 2016, the last year I did the survey. We started including special topics in 2002 to keep interest up. Several of them are examined below.

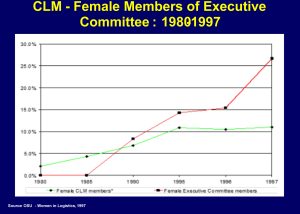

Surprisingly, or not so surprisingly, women held proportionately higher percentages of offices in NCPDM/CLM, both at the roundtable and national/international levels. In fact, the percentage of female members was soon crossed by the percentage of offices held around 1988 and was over 25% by 1997, surpassing the percentage of female members of 12.1%. (See figure 2.)

Figure 2: 1997 survey

Several local groups formed Women in Logistics organizations in the US and UK to provide guidance and assistance for navigating the corporate ladders.

In 2012, Ann Drake started AWESOME (Achieving Women’s Excellence in Supply Chain Operations, Management, and Education; https://awesomeleaders.org/ as she was retiring as CEO of DSC Logistics. Their first conference was in 2013. This group has lasted. It has sessions at the annual meetings of the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP, current name for our organization), has separate meetings, and presents awards for accomplishments.

What are the perspectives and attitudes of the female logistics executives

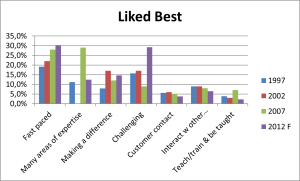

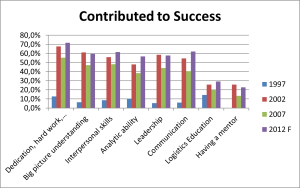

The most consistent questions asked in this section relate to what was liked best, liked least, and what contributed to success. Let’s look at 5-year intervals from 1997-2012 and note the relative consistency of responses.

What is best and least liked about being a logistics/SCM professional

Over the 2 decades of the survey, respondents would periodically reorder the list of items most and least liked that were generated from open-ended questions on the 1997 survey. In general, the order was often as displayed in Figure 3 for the 5-year comparison. In general, female logistics executives liked the fast-paced, changing environment and that many different areas of expertise are needed to succeed. They also liked the challenge and the opportunity to make a difference.

Figure 3: 5-year comparison

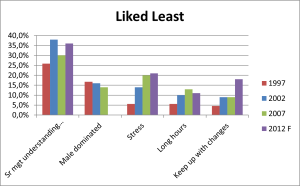

What they disliked most included lack of senior management understanding of logistics, as well as the stress, pressure, and demands of their positions. See Figure 4.

Figure 4: 5-year comparison

What has contributed to professional success

As will be discussed later under leadership, the factors listed that respondents felt contributed most to the success of the female exe- cutives are more the soft skills than the analytical training, although competence, such as analytic skills, should be demonstrated. The softer/strategic skills include dedication, hard work, and determination, as well as a big picture understanding, leadership, and interpersonal skills. See Figure 5. These categories were also derived from an original open-ended question in 1997.

Figure 5: 5-year comparison

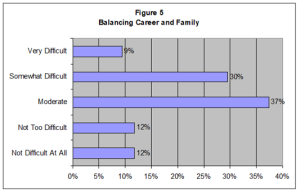

Balancing Career and Family Life

We asked this question in virtually all surveys. Although there were some differences from year to year, generally women found this challenge moderate, difficult or very difficult to manage. Around a quarter or less felt it is not that difficult or not difficult. Figure 6 is from the 2011 survey.

Figure 6: 2011 Female survey

In 2011, we asked respondents to comment on the most challenging aspects of career/personal life balance by stages of family life cycle. We also asked respondents to comment about their family obligations to gain a better comprehension of their experiences.

Stage of family life cycle

Respondents indicated challenges related to family obligations at different stages of the family life cycle. Almost one third (30.4%) of respondents mentioned family obligations in the early stage of parenting and 25% indicated that the middle (teen) stage of parenting also requires a lot of extra effort. Only 13.4% indicated challenges when in a relatively steady state in their careers. Interestingly, 31% of respondents noted that the strains of work/personal life balance had not really changed that much by stage of family life cycle.

When asked to comment about family obligations related to care giving, many noted that they had responsibilities for small children, grandchildren, dependent adult children and teen-aged children at the same time. Another significant group noted responsibility for aging parents, spouse, and grandparents. Respondents noted an on-going responsibility for family throughout their careers. Increasingly too, many appear to have joined the sandwich generation, meaning they have responsibility for both aging adults and children.

To be sandwiched between care giving responsibilities of both children and aging adults while trying to negotiate a very demanding career is causing strain. Some respondents noted that they found it easier to be career focussed prior to having their families. Many respondents noted that they had to make many personal sacrifices and found balancing work and personal lives very challenging to maintaining relationships.

Some have deeper challenges as they manage their careers as single parents. The demands of work in the logistics and supply chain field requires lots of overtime and often international travel making the management of schedules with spouses, children’s school and activity schedules and aging parents very difficult. There were some respondents that noted that they had opted out of having a family entirely due to perceived stresses and strains.

It is not surprising, given our earlier comments regarding the stresses and strains of balancing and managing work and personal lives, that respondents would find it challenging to fit one more element into their lives. For the 41% who wished they could study outside of workplace, many commented that they could not study due to a lack of time or access to financial or practical support. They did not feel they could juggle one more thing given workloads, extensive travel requirements and lack of energy. While there were some respondents working on education programs, others had decided to put off further education to a later stage of family life cycle.

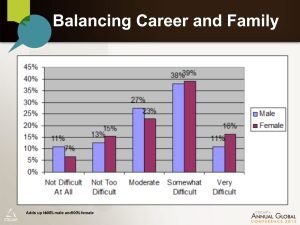

In 2012, we started surveying women and men and did so for the remainder of the survey years. Some women were upset to find out that men identified balancing work and family with a similar frequency as the female respondents. Overall, 49% of men identified the challenge as difficult or very difficult, whereas 55% of the female respondents felt so. (See Figure 7.) Women voiced their issue with the results at the presentation at the annual conference. Women are expected to work, as well as take care of their homes and families. How could the men feel similar pressures? Of course, one’s very difficult opinion may be different form another’s but it is clear that men are perceiving work-life balance issues, especially as domestic and child-rearing responsibilities are being shared more by men in some instances.

Figure 7: 2012 Survey

Mentoring

One of our special topics was utilizing mentors, which was the special topic of 2002. We asked a set of mentoring questions every year starting in 1999. The 2012 survey indicated that 75% of females felt that they had had a mentor, with 33% of mentors being female. The mentors provided assistance in the form of guidance, advice, constructive criticism, moral support, understanding politics, networking, and help finding a job, from most frequently to least frequently listed. 74% of respondents had mentored others. These percentages did not differ much over the time period of the surveys.

Besides reviewing resumes for students, I tried to impress the importance of finding a mentor, either inside or outside the organization and probably also a mentor not assigned by the firm. Mentors can be helpful if listened to and their suggestions acted upon, although a wise individual has many counselors to gain different perspectives. There are many land mines to avoid. More comments about mentoring later.

One of the speakers at the 2012 presentation suggested that we need to consider getting a better handle on the true differences between the views of men and women and understanding how these issues are perceived differently across age groups. While individuals differ, there are still similarities across demographics that can enlighten how to interact. There are many good books on relationship, leadership, and mentoring. A successful professional reads and applies, not just reads.

Your Brand

It is important to establish your own brand, especially in this time of frequent job hopping by the younger population. Each of us has a brand whether we want to acknowledge it or not. However, be careful. I remember counselling graduate students on the importance of their brands and then going to the bathroom afterward and seeing that the tag on my jumper was sticking up in the back. Being able to laugh at yourself helps.

Leadership and Legacy

The 2006 special topic was leadership. As women move up through the ranks, their ability to lead others is critical. The questions were derived from the writings of John Maxwell (primarily 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership and the 360 Degree Leader) and input from some women in logistics. The 360-degree aspect of leadership, according to Maxwell, is that you should lead from wherever you are in an organization and in all directions.

The respondents come from different industries, geographical regions, management styles, and organizational positions, just to mention a few. However, the responses are very consistent for most questions. Questions in this section related to key aspects of leadership that help the executives perform their responsibilities and the characteristics that contributed to these achievements, stumbling blocks, and the kind of legacy the executives would like to leave.

Most respondents (94%) see themselves as leaders even though most feel that they have not yet reached the top of their careers. Fortunately, most respondents (89%) appear to comprehend that they do not have to be at the top of their organizations to lead others, that they should try to lead (93%) when not at the top, and that they should not wait (95%) until getting near or at the top to learn how to lead. Two-thirds (65%) also realize that it takes time to learn to be a leader.

Key aspects of leadership: The responding executives are generally willing (86%) to share responsibilities and power with their people and know that true leadership is influence (73%), not position or title. Most executives (86%) feel that they are good managers, 92% view themselves as good planners, and a similar percentage (94%) are good at multi-tasking. Two-thirds (66%) indicate that they are good at setting and keeping priorities but 25% strongly disagree that they can prioritize well. However, these executives also comprehend that leadership is more than management with 89% agreeing that they both lead and manage.

The personal relationship aspect of leadership is evident in 98% of respondents feeling that they add value to their people and organizations. About three-fourths (73%) agree that they need to focus on leading themselves well before they can lead others since people follow leaders because of who they are. Female executives (87%) do their best to apply the golden rule with everyone in their environment, 95% help their people succeed, 82% connect with them before leading them, and 91% strive to be compassionate toward others.

In 360 Degree Leader, Maxwell emphasizes that one can lead from wherever one is and should consider not only subordinates, but peers, and those in higher positions for leadership opportunities. Female logistics executives (81%) feel that their peers value their leadership. The executives generally take on extra responsibilities (85%) to assist their leaders and 94% work to help their bosses succeed.

Ask to assist. Many may not think it is their responsibility to ask their leaders how they can assist with the leader’s tasks, but the survey respondents are willing to do so, and Maxwell suggests it if done for the right reasons. Do your own work first before volunteering. This can put the volunteer in a position to be noticed by leaders and appreciated for assistance with the tasks they face, making her more valuable to her leaders. When her leader needs assistance, he/she will know on whom to count. This can help position the logistics professional for support from the superior for a promotion.

Two-thirds (66%) comprehend that it is important to champion their leaders’ vision at some level even when they do not agree with it and 92% will support a vision they did not help to create. One should not blindly follow leaders but once a course has been decided that is within ethical bounds, the executives will assist the organization move forward even when they don’t think the stated vision is the best path.

Training has played an important part in the female executives’ successes, according to two-thirds (68%) of respondents but it is not the only factor. Good (52%) and bad (27%) timing have been important factors for some but not others.

Good leaders have several characteristics beyond the basic management skills. Trust is very important to virtually all (99%) respondents. Another is intuition (88%). Respondents know that moving up the ladder takes effort, a willingness (86%) to do whatever it takes, being a team player (97%), and being a go-to player who can deliver (96%). A greater challenge is being able to train other leaders since achieving great objectives takes not only leaders, but teams of leaders. Female executives are in the middle as far as their personal achievement in this regard with 83% either neutral or agreeing that they can get explosive growth by training leaders. There is more agreement with 88% viewing themselves as strategic, big-picture thinkers. Being able to encourage and motivate one’s team is important, such as 90% looking for ways to achieve victories, especially crucial at the beginning of projects, and 82% being able to energize the team. The leader sets the tone for the team and the mix of members affects project success. Attracting others to the team who are like the leader is good (32%) as long as not all have the same skill sets and personalities. Executives tended to avoid the extremes, strongly agree, or disagree, in their responses to this statement.

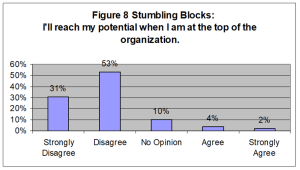

Stumbling Blocks: Female executives were asked to what degree they felt several factors and conditions they encountered as leaders were stumbling blocks. Trying to lead from the middle of the organization is viewed as a stumbling block by more than half (61%) of the respondents. Following an ineffective leader can be demoralizing, according to 73%. Meeting the sometimes-conflicting expectations of many constituents is challenging. The female executives’ responses varied regarding how much each of the following represents a stumbling block to their leadership: meeting the expectations of the leaders at the top (62%), working for female executives (22%), customers (33%), and vendors (21%).

Working with peers is not necessarily viewed as an issue for 58% of respondents. There are varied opinions on whether a leader’s potential is determined by those around her, with 56% agreeing and 33% disagreeing. The question did not state whether or not those around the leader were chosen by her. Also, responses varied concerning the leader’s potential being limited by the resources available with a 41%/47%, agree/disagree bimodal split. Many respondents (63%) felt that they faced an old boy’s network or stereotyping that can hinder their leadership.

Personal characteristics can make or break those in leadership roles. Most (87%) feel that their egos do not get in the way. Many (71%) do not think that their abilities and personality put limits on what they can achieve. Respondents (89%) feel that they can influence those around them and generate momentum (81%) to accomplish projects.

Perhaps since most respondents are advancing in their careers, they have a sense of the weight of leadership when others might just see the glamour of position and title. There were mixed responses to having more freedom as one moves up the organization with 52% expecting greater freedom (Figure 8). However, only 3% feel that they will be in control at the top and only 1% indicate that they will reach a point where they are no longer limited. Most (84%) female executives disagree that they will reach their potential when they are at the top of the organization (Figure 8). Hopefully, that means that they can reach their potential at other levels of the organization.

Figure 8: 2006 responses

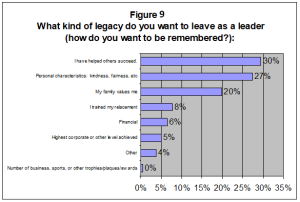

Legacy: Respondents were asked to choose only one legacy they would like to leave to the world. Figure 9 indicates the most-frequently selected legacies were helping others succeed, showing kindness and fairness to others, and that their family valued them. While all of the alternatives might have been checked if that had been an option, the personal impact factors rated higher than helping to train one’s replacement, financial or positional achievement, or number of awards/trophies.

Figure 9: 2006 responses

Taking Care of Yourself

To be able to perform at our best, we need to allocate time for ourselves. Here are some comments we received in surveys or from guest speakers in our CSCMP presentations.

2011 – Most challenging part of your career thus far and how you dealt with it: In addition to work and personal life challenges, many respondents noted continuing difficulties associated with the male dominated nature of the field, international travel requirements and the political nature of workplace environments.

Some examples given to describe challenges associated with the male dominated nature of the field included the ‘lack of room’ for women. They felt that they had to work in the ‘shadow’ and ‘harder than anyone else to be noticed’ or break through the ‘glass ceiling.’ Respondents noted that they felt discriminated against as being either the ‘youngest’ or ‘oldest’ person or assumed to ‘not know anything’ when they joined the organization. Related to such comments are those dealing with the need to learn how to ‘navigate politics’ that may be based on gender differences and/or the culture of the organization and professional field. These data are a decade old. Hopefully, it is better now in many cases as more women are in the workforce at higher levels.

Work and personal life challenges once again were described. Respondents noted the need for ‘constant juggling’ of demands, moving family due to multiple relocations over a short period of time, matching children’s schedules to work schedules and generally, the inability to take on as much.

Many noted the need to learn their way through the challenges when answering how they dealt with them. Some decided as a family to have one be a stay-at-home parent, to step back in their career plans to give the time needed to their families or to change careers and/or employers to find a better fit. There were some respondents as noted earlier, that chose to remain childless to enable a full focus on their careers.

Overall, there was a sense, too, of perseverance. Respondents were committed to their careers and life choices. They described learning as a way through the challenges. Many were finding ways to develop new skills on the job, negotiating their way through the politics, learning the cultural rules by job shadowing, taking on new projects and discussing ideas with colleagues. Some had the benefit of studying part time on MBA’s and PhDs. Regardless of the path taken, the respondent group appeared highly interested in their professional development through on-the-job learning as well as through educational credentials.

What mentoring you received and gave to others to assist with career challenges: Respondents noted that they received mentoring on issues already noted above such as how men think, how to deal with politics, work, and personal life balance. When describing the mentoring that was received and given, most respondents discussed mentoring in three different areas: networking, political maneuvering, and learning.

With respect to networking, respondents described mentoring as being introduced to the ‘big picture’, the industry, how to build a personal network to advance one’s career, how to find success in large or global organizations and how to adapt to a new culture. They were also advised to join clubs of different types, ask for advice on how to deal with uncertainty, negotiate career paths, and gain encouragement and support from the mentor. Thus, the role of networking was based on building collegial relationships as well as gaining access to learning opportunities.

Learning was another key category. In addition to learning via networks, respondents described other forms of learning received and offered through mentorship. They listed the need to share how a career in the industry plays out and where to gain advice. They talked about how to develop professional conduct skills; handle specific issues such as conflict, strategic thinking, and situational analysis; where to gain technical aspects of the field; techniques for brainstorming and providing constructive criticism. They also described mentorship as a vehicle for how to gain experiential knowledge such as leading others, how to approach international assignments, specific challenges with new business units, building confidence and so on.

The third key category noted by respondents and associated with both networking and ongoing learning is dealing effectively with politics. Many noted the importance of learning how to maneuver politically, deal with difficult people, build relationships, navigate the terrain with executives, build political/social/networking skills, and become savvy in order to make the next move. Politics appeared to be a huge issue for many respondents and much of mentoring given and received seemed to deal with how to network and learn related to workplace politics.

Most effective pieces of advice they had received relating to work/personal life balancing: Most respondents did provide advice on work and life balancing that they found most effective. Many described the need to set clear boundaries and priorities learn to say “NO”, stay positive and motivated and take care of oneself to be able to take care of others. Another key message was that it is important to manage your home life as well as your work life and that happiness and productivity at home spills over into work life. Many suggested sentiments about the importance of putting family first. Some of the comments include:

“Don’t commit yourself to anything to such a degree that you can’t live with the results”

“Work will be there tomorrow, time with family may not!”

“Nobody lies on their death bed wishing they’d spent more time at work”

“Your work will not be your legacy, your family will!”

What respondents wished that they had learned from mentors regarding how to deal effectively with work/personal life balance along with their biggest challenge and success in this area: Most wished that they had received advice on how to balance their work and personal lives effectively. They noted the importance of a disciplined approach to maintain both their work and personal life balance and protect their family relationships.

Many mentioned that it would have been useful to know how to make family decisions without jeopardizing their careers, keep their marriages thriving while careers advanced, to know how to switch off during vacations, how not to bring frustrations home and how to make relocation easier on their spouses and children. There were comments about how to deal with guilt, take vacations and spend time with the family without guilt as well as do what is required at work without guilt about not spending time with family.

Other aspects of advice thought useful were how to negotiate jobs and salaries, manage priorities, network, deal with male egos, get support from other women, compete in a male-dominated field, and learn about politics early in career to avoid missteps.

How respondents would mentor others: We asked what advice they would pass on regarding how best to balance work/personal life – something that they wished they had known earlier. Here is where respondents really shared their thoughts and advice with a goal to mentor others on what they wished they had known earlier. Their advice is presented in three groupings below: taking care of yourself, taking care of your career development, and setting clear priorities.

What key organizations they would recommend for those professionals coming up behind them to help address their work and personal life issues: They offered the following advice. First seek out many informal and formal connections. Such connections can be other women peers and/or supervisors, someone you can trust and respect and ask for their opinions. These women will be a great source of insight into how you can manage things in your field. You can seek out the senior women in your organization and get their thoughts on how they managed the challenges or get a life coach who can help you work through them.

Second, join professional organizations to network and meet other women in your field. Many respondents noted that the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) is an organization that can help with networking. Other organizations were also mentioned.

Concluding Comments

We express much gratitude for the female, and then male, logistics/SCM executives who took the time to respond to our surveys, some over multiple years. The last survey of the CSCMP membership that I did was in 2016. I had retired and respondent numbers were dropping. People get too many surveys and especially don’t like to answer the same questions year after year, although we would always have a special topic to provide some differences, such as mentoring. The 1997 response rate was 11.2%, while the 2016 response rate was 6.1%.

Respondents were mainly managers, directors, or higher-level positions in keeping with the general membership of the organization. Forklift drivers, dispatchers, etc., were not included in the reports so interpretations of results should keep this in mind.

At the 2023 CSCMP annual meeting, the educators, for the first time, inducted 20 people who had contributed to the early development of the field. Four of us are female. This will grow over time as we induct more recent contributors.

As our professional organization has grown and changed names three times (NCPDM –> CLM –> CSCMP) the contributions and recognition of women in the field have also grown. While people will still notice differences in age, height, weight, race, sex, etc., it is our hope that we are closer to Martin Luther King’s statement, paraphrased: “We look forward to the day when all people are judged by the content of their character, rather than the color of their skin, sex, etc.”

_______________________

References

Cooper et al., All surveys from 1997 to 2016. Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (or predecessor Council of Logistics Management), Annual Proceedings.

Maxwell, John C. (1998), The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership: Follow them and People Will Follow You, HarperCollins Leadership

Maxwell, John C. (2011), 360 Degree Leader: Developing Your Influence from Anywhere in The Organization, HarperCollins Leadership